EXHIBITIONS

Hiroko KUBO “ISAAC”

- Information

- Works

- DATE

- 2022-12-09 [Fri] - 2023-01-22 [Sun]

- OPEN TIME

- 11:00-19:00[wed-sat] 12:00-18:00[sun]

- CLOSE DAY

- Mon, Tue, National holidays, 2022/12/26-2023/1/10

Artist’s statement

In January 2018, my son was born. In January 2020, a virus began to spread throughout Japan. In February 2022, a war started in a neighboring country.

Facets of my life and society have changed dramatically just in the past few years.

Whereas a child’s day to day is full of possibilities and can accomplish today what was not possible yesterday, It feels as though society is moving in opposite direction.

A pandemic, wars, climate change, inequality – and all the theories (accelerationism, degrowth, technology, posthumanism, etc.) that would seem to have the answers to the anxieties that appear before us, offer no bright prospects for the future.

To quote the author of “The Complete History of Sapiens”, Yuval Noah Harari:

“We should never underestimate human stupidity.”

Evidently, the era of homo-sapiens, with a history of 200,000 years is coming to an end and that end is closer than we can imagine.

Standing on the edge of despair and looking ahead, what do we see and do from here? Faced with this grand question, I think about what I could do and my answer remains the same. It is to represent the era that we live in, with materials that are available now – in sculpture, the practice that I’ve followed through the years. This is because I, myself have been inspired by the sculptures of our predecessors who have taught the mysteries of being born and to live as a human being.

I refer to artifacts displayed in museums of history and archaeological sites as models for my own work.

Seeing that it’s impossible to measure the value of thousands or even tens of thousands of years when they were created, there are still moments when these “things” transcend time and space to convey something to us without fail. As it is believed in Christianity that “In the beginning was the Logos(word),” I believe in what the ethno-arts scholar Shigenobu Kimura advocates: ”In the beginning was the image.”

Sculptures, like people, have volume, exist in the same physical space, and will weather and break down under the same physical conditions. This ephemerality and fragility is what I love about sculptures. At the same time, the fact that it has survived in the world for tens or hundreds of thousands of years by the will of our ancestors (sometimes by accident) shows the strength in this form and is one of the driving forces behind my continued work in sculpture.

ISAAC is one of the the founding figures in the Old Testament and is often used in the west as a first name for men, especially Jews. It is pronounced variously in English as Isaac, in Hebrew as Itzhak ( יצחק†), and in Greek as Isakios (Ισαάκιος) and in Japan, it reads Isaku. While considering a name for my child, a book by Isaku Yanaihara on the bookshelf by chance, came into sight. He was a philosopher and a friend of the sculptor Giacometti. Curious about the unfamiliar name “Isaku (Isaac)“ I looked it up and learned that its etymology means “he laughs”. I took to this name which is used all around the world and yet has somewhat of an old Japanese ring to it. There, I decided to name my son “Isaku (伊朔)”.

Yanaihara states in his book, an inscription of his conversations with Giacometti:

“There is no development or progress in the history of art. There is no repetitive stagnation. There is only decline and fall.” (Dialogue with the Artist, 1984)

What kind of world will my four-year-old son see in fifty or even a hundred years?

I hope that in the distant future, grand creations will stand the test of time to offer something to humanity and to the meaning of life. (or to future hybrid-human?)

It would be of great privilege to me if I could help in this regard, to stand with our homo-sapien predecessors who have bequeathed to the world such wonderful images.

2022

Kubo Hiroko

Tangibles: Forms Dance Across Boundaries

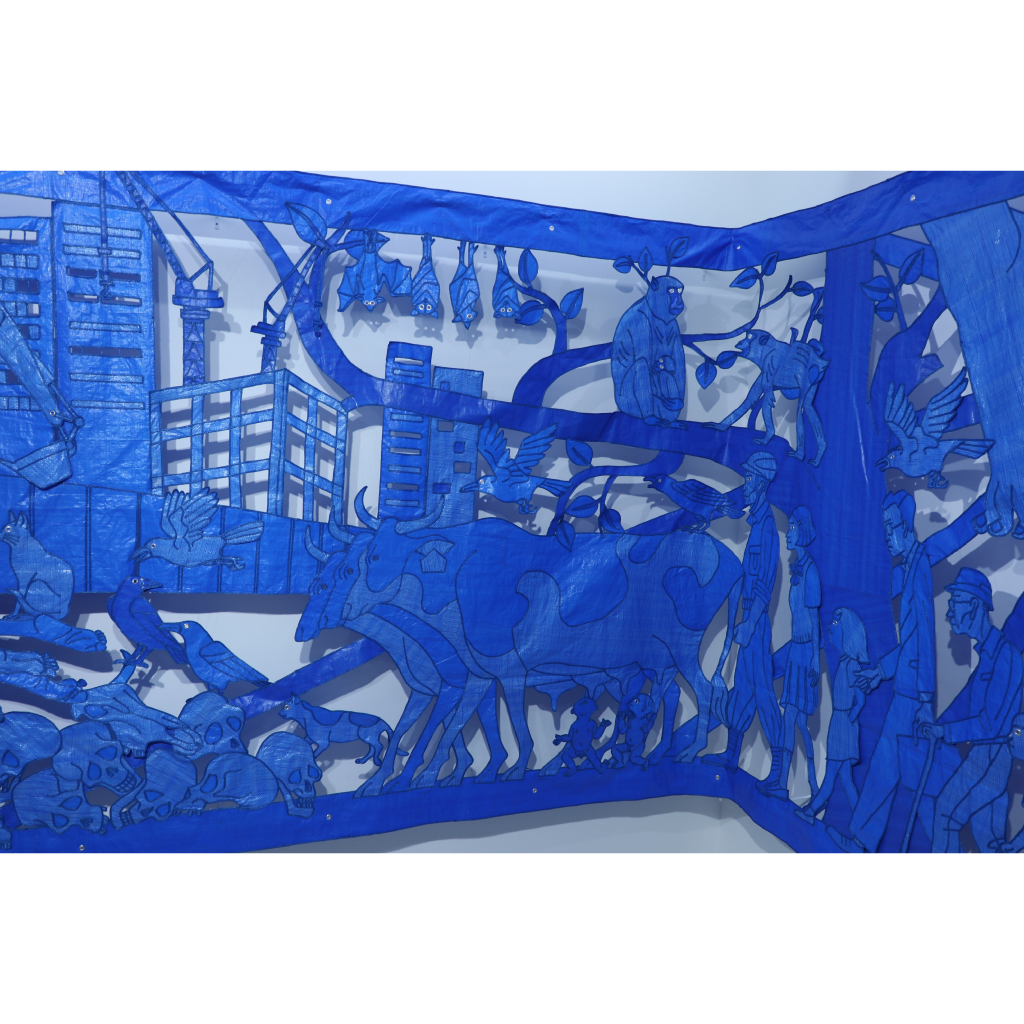

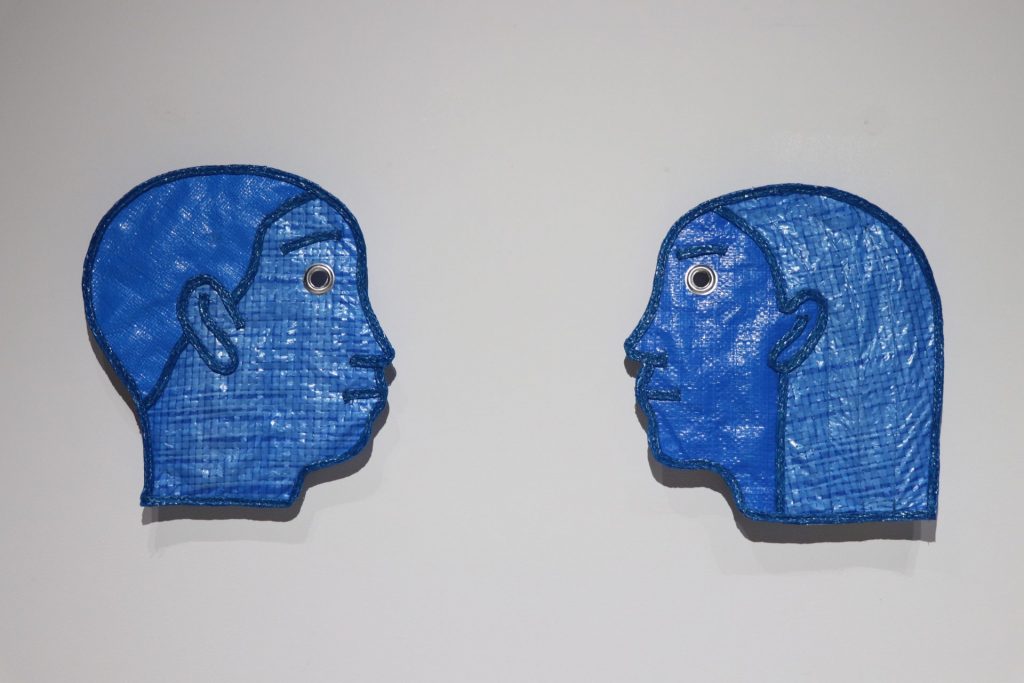

Applying traces of folk art, prehistoric art and theories of cultural anthropology as pointers, Kubo composes her interests in agriculture and idols in the form of sculpture in a unique way.

Her works and practices are not limited to human privilege or fixed frameworks of modern thoughts and representations, it also puts non-humans in perspective.

Growing up in the mountainous region of Hiroshima prefecture, Japan and currently living and working in Hiroshima City (1), Kubo had an opportunity to see from a far, her native land while completing her Master of Fine Arts degree in Texas. It was there in the hot and dry climate where minimal art can be found displayed in abundance, the polar opposite of all the familiarities of home. Realizing such contrast, Kubo strongly recognized that she, as a Japanese woman, is indeed a marginalized presence including the world of art, dominated primarily by white heterosexual men. Through her first-hand experience, Kubo observed the necessity in her praxis of dismantlement and reconstruction of the cultural representations that are formed within the context of specific historical perceptions and power structures through heterogeneous periods and historical concepts. Her practice revolves around re-imagining and visualizing other possible narratives incorporating these fragments.

Kubo’s early work Cultivated land (2013), created right after her experience in the U.S., where Christianity is strongly rooted, uses scrapped daily necessities and water to reflect the animistic idea that all things can be gods, contrary to monotheistic religion. In the following Urban Cultivator (2014), presented in Guangzhou, China, she zoned in on the imbalance brought about by rapid economic development between rural areas and large cities. With Muddy feet (2015) which was presented at the Setouchi Triennale in 2016, she explored the damages caused by wild animals in rural Japan, where the population is excessively declining.

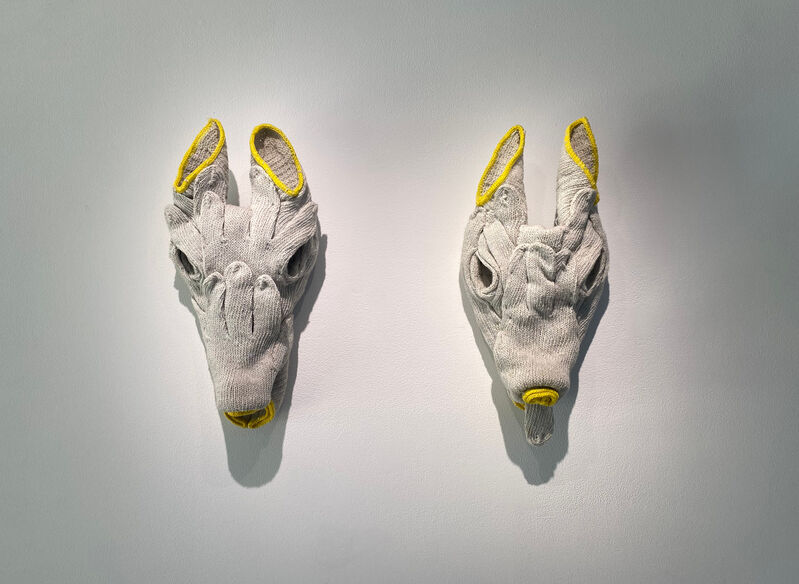

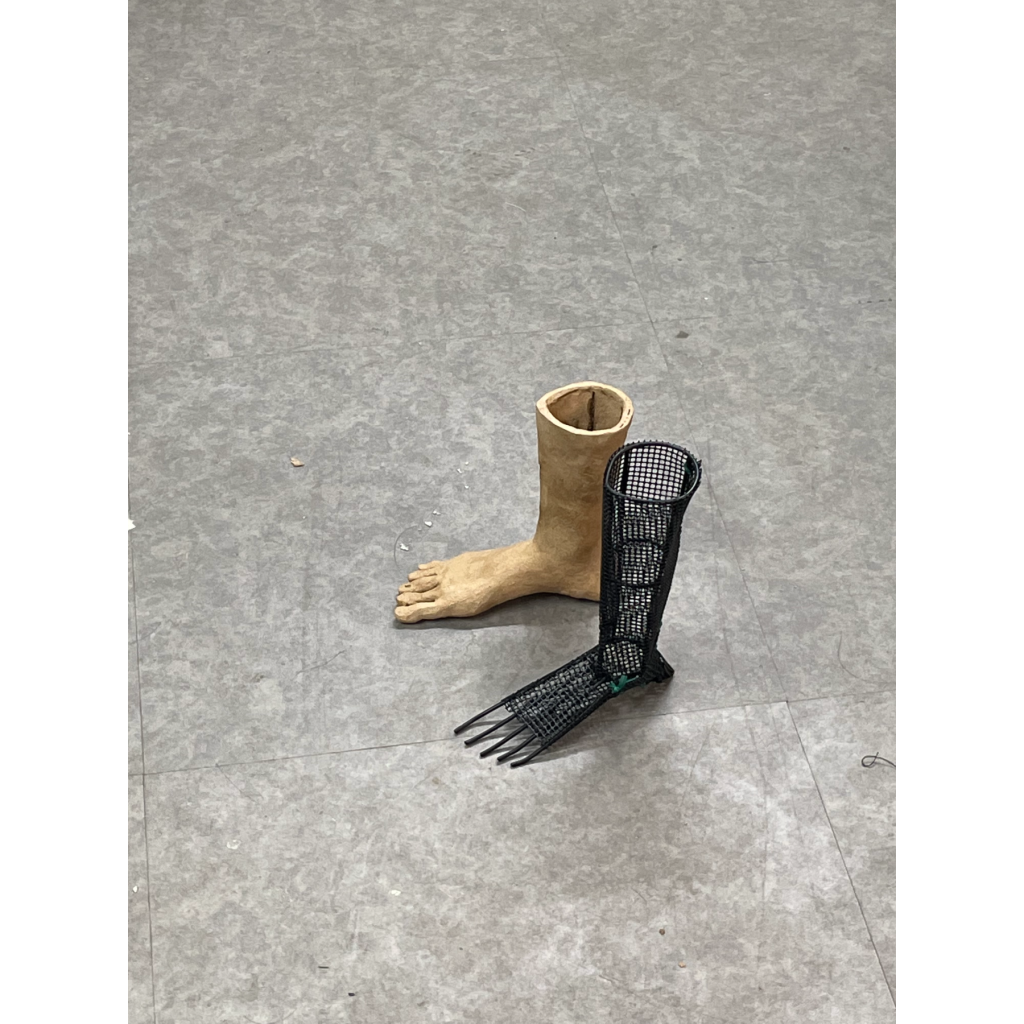

While implementing easily accessible iron and windbreak nets as material, this work is a tribute to the labor and production that has been practiced in the area for many years, also a representation of the confrontation and symbiosis among the threat of nature that has continued since ancient times. Kubo’s use of mass-produced industrial materials, lightweight, hollow, and framed sculpture is also a counterpoint to the authoritative, masculine, heavy, and waste-producing attributes that have been cultivated throughout the history of sculpture.

In her text “The Goddess of Bricolage,” written in occasion to her solo exhibition in 2017, Kubo adopts the concept of bricolage, used by cultural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss in his “The Savage Mind” to illustrate the mythological thought as a method for her own handiwork and a way of thinking. Kubo believes that fragments of thoughts obtained through the universal act of making things is to reconsider the history of the sculptural image. In her “The Statue of Heinuwere” (2020), which attempts to examine the four disassemblages in sculpture, she draws attention to a theory in connection with mythology, pointing to Jomon figurines that represent women commonly missing their extremities. It explores the powerful presence and energy of fragments and imperfect shapes, and its narrativity that can be seen through their destruction, weathering, and rebirth.

Her perspective on the nature of objects open to interpretation, and the relationship between agencies and human society, is further expanded in this solo exhibition entitled “ISAAC”. The state of exception that the pandemic has plunged the entire world into over the past two years, has shaken the very crust that conditions the potentiality of thoughts. Re-examining where we now stand individually and as a community, the exhibition attempts to unravel these complex, invisible distortions through concrete narratives and embodiment that reflects Kubo’s investigations in tangible forms. In a space that would normally be well suited for a natural history museum with artifacts in mind, the works presented are open to interpretation invariably and are in the process of becoming. Their heterogeneity and plurality of time, tied to a specific times and places, allow the viewer to escape from the suspension of a particular cultural identity, and encourages new imaginative power.

Noriko Yamakoshi (Co-Curator)

Noriko Yamakoshi

Independent curator, writer. Recent exhibitions include: “Games.Fights.Encounters” (2020-2021), ”Choreographing the Public” (2019-2020). Co-writer of “la_cápsula – between Latin America and

Switzerland: An Exploration in Three Acts” (2020), an interview essay “<MJ> Yuichiro Tamura” (2019), among others. She holds a master’s degree in curation from Zürcher Hochschule der Künste.