EXHIBITIONS

Keisuke Kondo and Motohiro Tomii ”Possibly a Human—Somewhat Classical”

- Information

- Works

- DATE

- 2025-10-10 [Fri] - 2025-11-08 [Sat]

- OPEN TIME

- 11:00-18:00[Tue-Sat]

- CLOSE DAY

- Sun, Mon, National holidays

Rather than offering a detailed explanation from the gallery, we believe the most straightforward way to introduce Possibly a Human—Somewhat Classical, the two-person exhibition by Keisuke Kondo and Motohiro Tomii, is through Tomii’s own curatorial proposal alongside the artists’ statements. Below we present Tomii’s text “About the Exhibition” in full, without edits. We invite you to read it in its entirety.

We hope this exhibition becomes a place where you can encounter the charm and joy of art.

About the Exhibition

Motohiro Tomii

For the publication of the catalogue documenting Plain and simple painting and sculpture that continues like an enigma in the background (Kawasaki City Museum and LOKO GALLERY, 2023), we decided to include not the photographs of ourselves, but portraits we made of each other (my sculpted bust of Kondo and Kondo’s portrait of me). What began as a casual whim soon led Kondo to explore portraiture in his solo exhibition, while I presented a piece on what I call my “B-side,” a piece verging on sculpture. We have had almost no experience depicting actual people, living or historical, which leads me to wonder why we now find ourselves drawn to portraiture. At the very least, I want to stress that—even if the works appear to resemble human figures—this is not a simple return to figuration. This exhibition is our attempt to pursue a more abstract engagement with the traditions of Nihonga and sculpture—traditions that we have willingly taken on ourselves as representatives of, regardless of public perception. One might say, “Then why not do it as a solo exhibition?” Yet we hope you will see our cautious choice to present it as a two-person show as itself an expression of respect toward portraiture. Half in jest, this is also our first “ordinary” two-person exhibition since we began collaborating in 2010. It feels like stepping into the ring for a singles match after years as tag-team partners. Whether it turns into tentative sparring or an intense battle remains to be seen.

Talk Event 1 “Classical Production”:

October 18, 2025 (Sat) 15:00–17:00

Keisuke Kondo, Hirohisa Tomii, Keisuke Mori (Curator, Chiba City Museum of Art)

Opening Reception: October 18 (Sat), following Talk Event 1

Talk Event 2 “The Écriture of Installation and Dismantling”:

November 16, 2025 (Sun) 15:00–17:00

Keisuke Kondo, Hirohisa Tomii, Tomotaka Yasui (Sculptor)

・It Might Be Him|Keisuke Kondo

・Seeing is Classical|Motohiro Tomii

・Raised onto the Stage|Takayuki Hayashi

Neoclassicism

“Neoclassicism” is the name given to a style of Japanese-style painting that came into full bloom between the late Taisho and early Showa eras. This style, exemplified by artists such as Kokei Kobayashi and Yukihiko Yasuda, placed strict linear draftsmanship at the core of composition. Combined with bright colors and generous blank spaces, it produced balanced, harmonious images. It marked both a new turn and, in some sense, a culmination in the development of Japanese-style painting.

The painters themselves never called their work “Neoclassicism.” The label was later coined by art historians as a way to sort and explain artistic tendencies. Inevitably, the retrospective naming did not perfectly align with the actual practice of the painters, and a certain gap emerged between term and work.

Even among scholars, the term remains contested. What the “neo” refers to is vague; the “classicism” has no clear point of reference; and the paintings themselves lack the internal coherence one might expect of a true “-ism.” Since the term is borrowed from Western art history, its use is somewhat ad hoc—though not entirely unfounded. Yet it is precisely this vagueness that has allowed the word to persist: a convenient, abstract shorthand that, however loosely, captures the character of these works.

Re-reading “Neo–Classic–ism”

The string of morphemes in “Neo–Classic–ism,” sits awkwardly together, its components ill at ease, as though faintly trembling, unable to rest in their given form. It is like pressing and holding the home screen on an iPhone: the neatly aligned icons begin to quiver, betraying their discomfort and hinting at a shift. In the same way, this compound word, caught in its vibrating state, resists settling into a single, fixed meaning. Instead, it sustains its ambiguity, holding meaning in fluid, shifting forms. “Neo–Classic–ism” thus embodies the inherent impossibility of definitive naming, even as it waits for the moment when it will be re-read and reinterpreted.

The painters associated with what is called “Neoclassicism” placed particular importance on lines. Their linework—often described as tessenbyo (“Wire-line drawing”), with its uniform, unmodulated strokes—appears expressionless, yet carries a quiet abstraction. On the pictorial surface, the lines are joined not so much by the imagery they form as by the tensions that bind line to line. This fills the surface with taut energy, which paradoxically gives rise to a sense of stillness. Yet when one lingers over that seemingly tranquil field, the lines begin to pulse, hinting at the possibility of being drawn anew.

Treating Tomii’s Portrait as a Classic

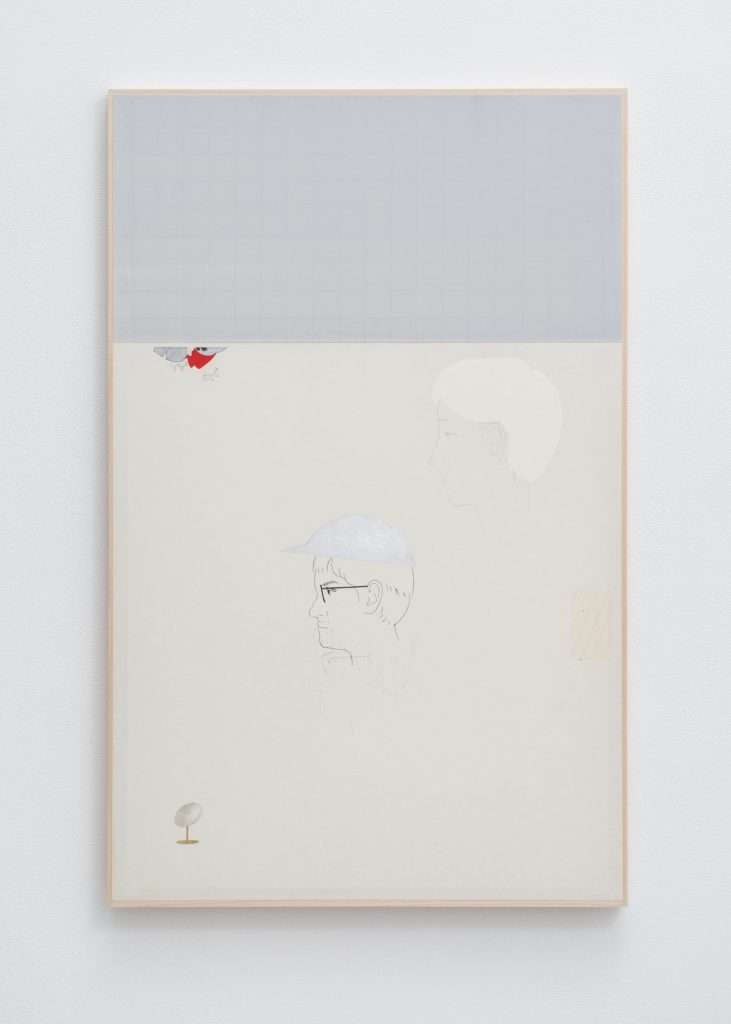

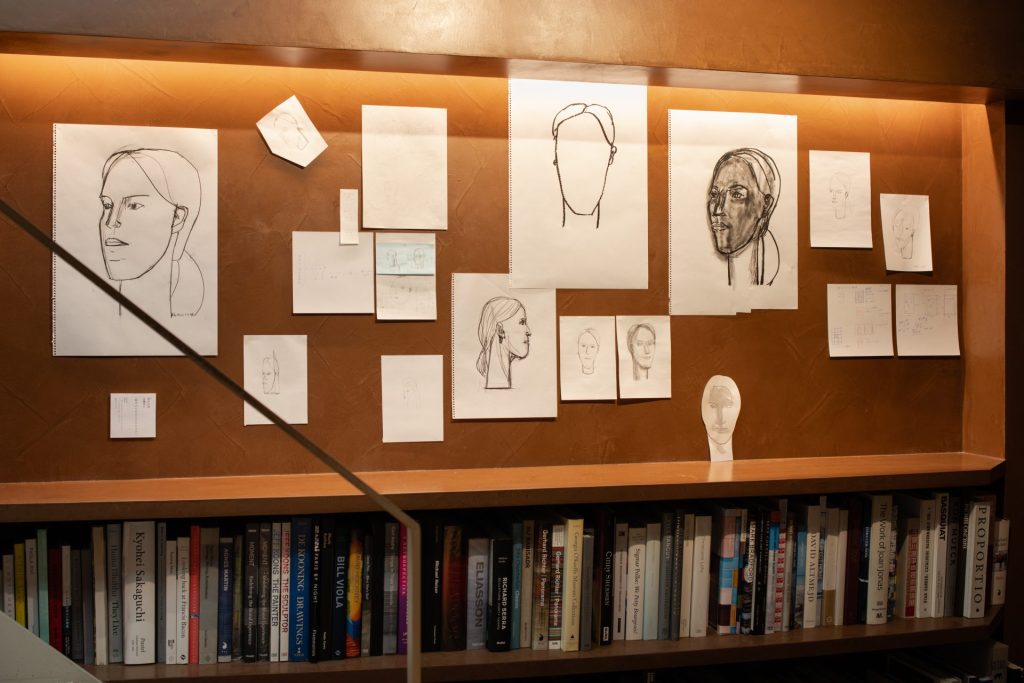

I drew Tomii’s portrait in 2022. For the catalogue of our two-person exhibition, we decided to portray each other —he made a sculpture of me, while I drew him. Using a photograph of Tomii taken in New York in 2015 as reference, I overlaid it with how he looked in 2022. The portrait came together quickly. It was built from lines abstracted from Tomii himself, yet I heard more than once that it bore no resemblance (though I think it does). So who, really, is this a portrait of?

For this exhibition, I intend to begin by copying that portrait of “someone who might be Tomii.” To copy a work is to take the original as a model—in other words, to treat it as a classic. And it is precisely because a classic remains open to being redrawn that it remains a classic.

Once the drawing is finished, I will photograph it with my iPhone and send it directly to Tomii.

June 23, 2025

Seeing is Classical

Motohiro Tomii

Seeing is the question—seeing is the problem. What do we see? By what means, from what distance, for how long? From which place, position, or circumstance do we look? What exactly are we seeing—or have seen? I create in order to understand this, but I still do not.

I don’t think it’s possible to represent what we see (or have seen) accurately. But maybe that impossibility is its own kind of truth. I find myself able to look at a work not only from the standpoint of making, but also from that of viewing. And there, again, the inaccuracy and even the dishonesty of seeing rises to the surface. In this tension I feel a certain soundness, but also an uneasy suspension, a kind of moratorium, which unsettles me. I want to hold both. Making, I think, becomes the act of keeping such contradictory sensations together.

Maybe my interest in these questions started back when I was studying figurative sculpture in college—that is, modeling in clay. No, not “maybe”—actually, I knew it for sure. But so what? Knowing that didn’t really solve anything. Honestly, it just meant I was scared.

Figurative sculpture is interesting. There are methods that can be shared: even when looking at and shaping the same subject, what emerges is different. If the purpose is only to master technique, those differences just end up as levels of skill, which isn’t very interesting. Of course, learning and practicing methods matters; they open up the world of dialogue. But methods and techniques aren’t things to be strictly followed—they are things to work with. They are not the same, nor entirely different. I think the point of figurative sculpture lies in this subtle sense—something that both maker and viewer can feel equally. Turn in any way you like, and you’ll find the human figure. The stubborn, tangled, classical relationship between people and figurative sculpture—bound up with seeing (or having seen)—goes on.

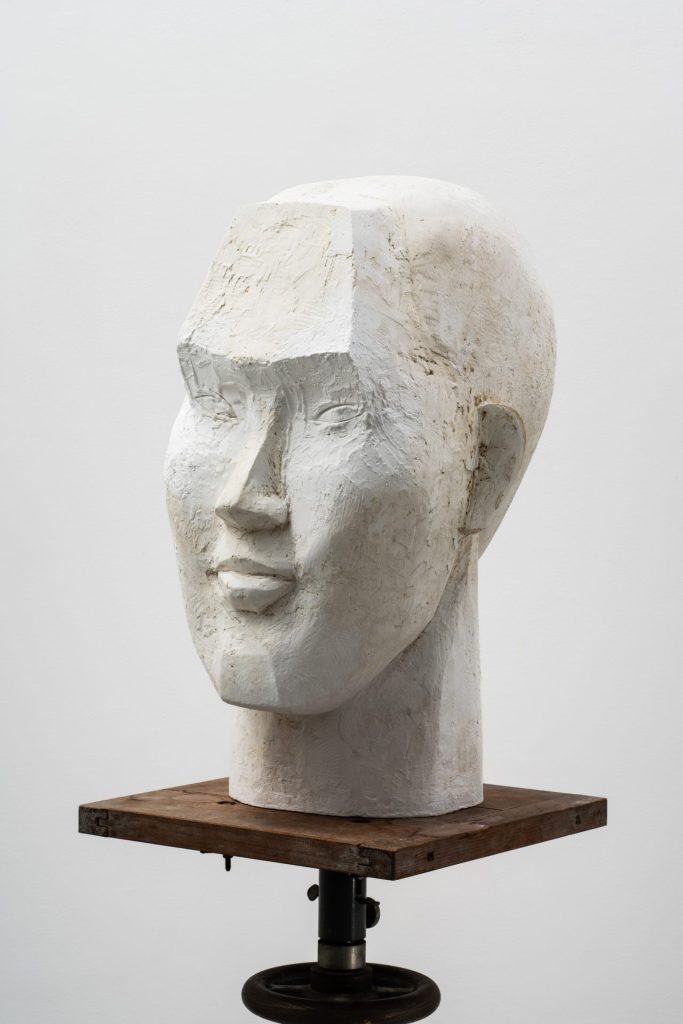

I’ve kept my practice at a distance from figurative sculpture because I wanted to relate to it loosely, in a kind of hit-and-run way. But now I want to deepen that relationship. What kind of depth it will take isn’t the point. To think about what my work has been and what it might become, I want to take it on “just once.” I want to face the human head—the bust, not the whole body. If the head were to turn into something abstract yet concrete—like architecture, or a spaceship—then would it not become something other than a person or a sculpture, but something else altogether: space itself, or a question given form.

All of this should have remained at the level of daydreams. But in 2022, when Kondo and I made portraits of each other, one thing led to another. And now I’m left wondering: What do I do now?

13 July 2025

Raised onto the Stage

Takayuki Hayashi

This time, the collaboration between Kondo, who works from a foundation of Japanese painting, and Tomii, who begins from sculpture, takes “the classical” or “classicism” as its point of reference. As I indicated in my previous paper*, if their last attempt was brought about by a instantaneous “line,” then there is little reason to be surprised by its development into the “classical.” Since Heinrich Wölfflin, one of the characteristics of the “classical” in art historical research has been considered to be its “linear” quality.

Yet their intentions diverge. For Kondo, the term applies to the works of certain Japanese painters, which he reproduces as specimens. For Tomii, it evokes figurative sculpture, particularly the portrait busts—sculpted heads that form part of the Western sculpture tradition.

As the old idiom goes, it’s as if they share the same bed while dreaming different dreams. Yet, it is precisely through such dissonance that the exquisite quality of their collaboration emerges.

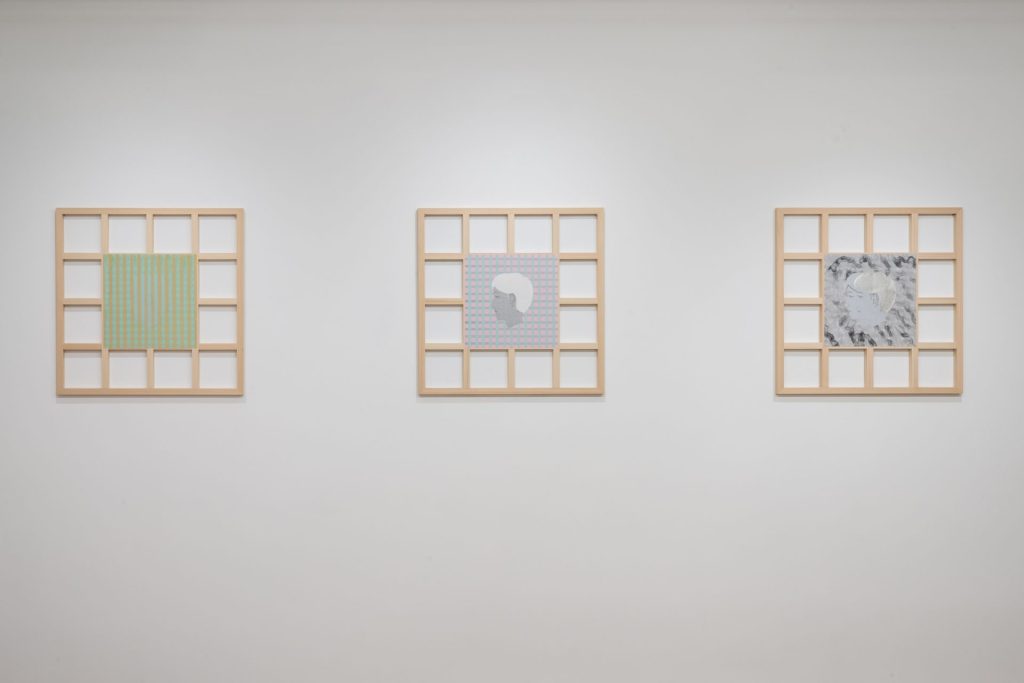

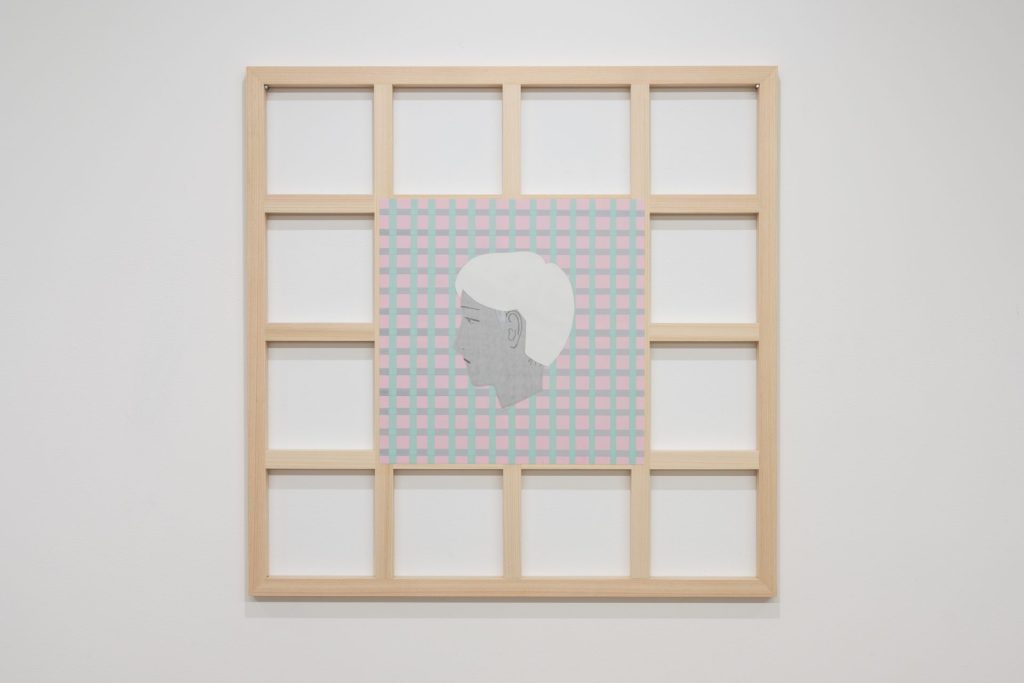

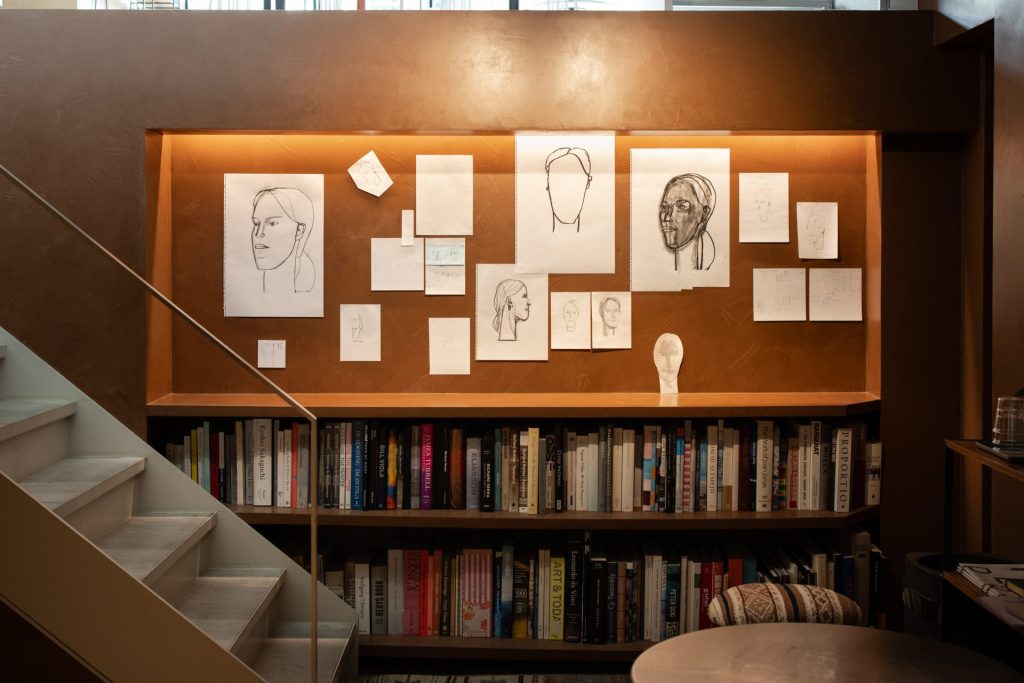

I have seen some of the works they plan to exhibit. In both artists’ practices, one can glimpse the development and subsequent shifts that have unfolded since their presentation here in 2023. Kondo has condensed the installation that he presented at Gallery αM in 2023 into the layered surfaces and reversals of a painting. Tomii, meanwhile, has shifted from the plaster constructions he showed at the Keio University Art Center in 2024—moving from linear frameworks to solid, modeled forms. This time, unlike before, their works seem unlikely to physically merge.

How will the dreams, pursued separately for a time, meet again in this place? Two patterns can be anticipated. One is the approach taken by artists in recent years like Pierre Huyghe, Dan Võ, or Ali Cherri, who use the sculptures of heads as key characters in their installation works (in Huyghe’s case, the heads are covered by Noh mask [Human Mask, 2014] , a beehive [Untilled (Liegender Frauenakt), 2012], etc.). These evoke mythological, ancient scene for the viewer rather than classical ones.

On the other hand, considering that Kondo and Tomii’s collaboration will be exhibited here at LOKO GALLERY, another anticipated pattern is the rise of an illusory space—indeed, a space recalling the stage of classical Western theater. The space has shallow depth and an extremely high ceiling. The exhibition space opens onto the upper floor through an atrium, and throughout these areas, various installations arise, each beginning from head images rendered in painting or sculpture. Both the images and the installations are abstract in that they refrain from overt description or explanation; instead, it is their visual form and presence that direct the movement of visitors—who, without instruction, will almost instinctively face what appears to be a face head-on. Alternatively, the grid supporting Kondo’s screen will guide our gaze along the vertical and horizontal directions of the wall, while some small facets carved on Tomii’s sculpture will sharply divert our gaze diagonally to the opposite side.

That place is a stage. Yet, it probably isn’t something that makes us, the viewers placed within it, the main characters or subjects—unlike those “immersive” or notoriously “theatrical” (Michael Fried) installations (a stage is not the same as a theater). Nor will it leave us as tranquil bystanders, as when we usually look at paintings or sculptures. We find ourselves raised onto the stage we thought was a distant illusion, and there, we must confront each work as an equal presence, each carrying its own persona. The heads are watching us.

*See my previous essay: “Between the Lines: On the Collaboration of Keisuke Kondo and Motohiro Tomii” (in Japanese, in Keisuke Kondo and Motohiro Tomii, Plain and Simple Painting and Sculpture That Continues Like an Enigma in the Background, HeHe, 2023)

Photographs by Dai Yanagiba

Motohiro Tomii《RV2501》2025, Plaster, 38×21×27 mm

Motohiro Tomii《RV2502》2025, Plaster, 65(H) mm

keisuke Kondo《Some Portraits 01》2025, Color on paper mounted on wooden frame, 75×47.6 mm

keisuke Kondo《Some Portraits 02》2025, Color on paper mounted on wooden frame, 149.9×115.3 mm

Motohiro Tomii《heads》2025, Plaster, 21.5×8×7 mm

右下|冨井大裕《モデル2512》2025, 陶 , 10.5×7.5×21 mm

Bottom left|keisuke Kondo《Statue of a certain man》2023, Color on paper * Quotation from Yasuda Yukihiko, “Fūrāi Sannin”, 29.2×21.8 mm

Bottom right|Motohiro Tomii《Model2512》2025, Pottery, 10.5×7.5×21 mm

Motohiro Tomii《RV2503》2018-25 , Plaster, 47.5×25×29 mm

Motohiro Tomii《StudyB》2018, Plaster, 48×17.5×22 mm

keisuke Kondo《Some Portraits 03》2025, Color on paper mounted on wooden frame, 53×53 mm

keisuke Kondo《Some Portraits 04》2025, Color on paper mounted on wooden frame, 53×53 mm

keisuke Kondo《Some Portraits 05》2025, Color on paper mounted on wooden frame, 53×53 mm

keisuke Kondo《A Painting of a Moment》2025, Color on paper(3 pieces)mounted on wooden frame, 18×53×10 mm*Stretcher size

Motohiro Tomii《Model2515》2025, Pottery, 11×3.5×4.5 mm

右|近藤恵介《冨井氏像》2023

Left|Tomii Motohiro, Mr. Kondo, 2023

Right|Kondo Keisuke, Portrait of Mr. Tomii, 2023

Motohiro Tomii・Keisuke Kondo, Exercise for Production, 2025