EXHIBITIONS

Fumiaki Aono “Each Planet and Their Inhabitants”

- Information

- Works

- DATE

- 2024-09-27 [Fri] - 2024-10-26 [Sat]

- OPEN TIME

- 11:00-18:00[Tue-Sat]

- CLOSE DAY

- Sun, Mon, National holidays

■ Talk Event and Reception Party: Saturday, September 28th, 15:00-18:00

Guest: Hikaru Ouchi (Curator, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum)

Participation Fee: ¥500 (Includes Booklet “Theory on Repairing“)

LOKO GALLERY is pleased to present Aono Fumiaki’s solo exhibition “Each Planet and Their Inhabitants”. This will be his second solo exhibition at our gallery since “Growing From the Valley: The Remnant of a Tate-mono (2022)”.

Aono has been focusing on the act of repairing since Remarks on Repairing (1991) and the text Theory on Repairing (1996). He continues to present large-scale works based on fieldwork, or pieces in which he meticulously restores fragments of lost property he has picked up on the streets and elsewhere that associates with memories and the past.

For Aono, the fundamental acts of creating, destroying, and repairing by humans cannot be simply separated, as he states at the end of Theory on Repairing, “The act of repairing is a metaphor for chaos/regeneration…It is the creativity that cannot be seen in the act of making, and that embodies the wholeness of life that is innate and unique to repairing.”

The artist’s initial approach was to avoid involving the background—the people, housings, the society and the environment—of the materials he gathered, as a noise and hindrance to practice the act of repairing. However, his approach shifted to consider the background of each material, or fragment to acquire true restoration. To connect each fragment became an act synonymous to connect each history, which increased the impact of his works.

By repairing a large number of diverse fragments that had gathered, especially after the great earthquake, he deepened the act of repairing to its origins to a level where, in the artist’s words, a “world of emotion” began to emerge.

The series of creative activities following one of his major exhibitions in recent years, “Mono, sleeping, Koejiyama, voice-over” (sendai mediatheque, 2019), is titled “comprehensive restoration”.

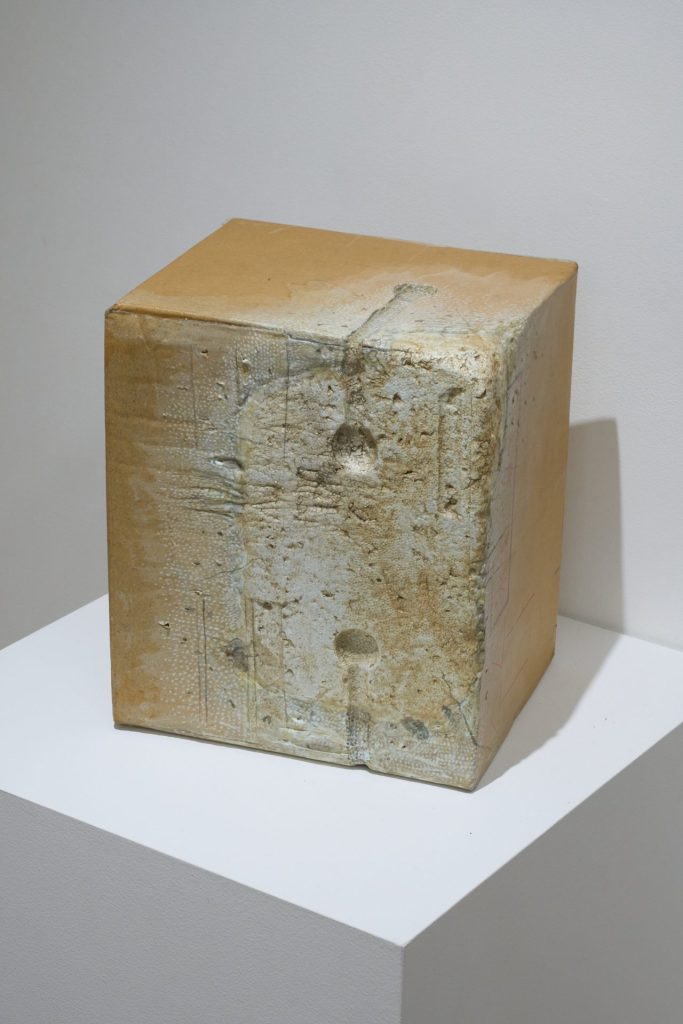

In this exhibition, the artist focuses once again on chests of drawers, which could be said to be the main material used in the series.

Secondhand chests used as material for his works has been lost, and what was supposed to be a solid object now gives a floating feel, almost like a planet wandering through space.

It is as if Aono is trying to recapture the current disordered state of the world from a planetary perspective.

On Saturday, September 28th from 3PM, we welcome Ouchi Hikaru (Curator, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum) to a talk event where she will guide the audience to unravel Aono Fumiaki’s perspective along with texts of Theory on Repairing. Please feel free to join.

“Each Planet and Their Inhabitants”

August 5 2024

Fumiaki Aono

Since some time ago, I have been using secondhand furniture (mostly chest of drawers) as a substitutional material or medium to restore various fragments or to create a derivative work from it. Moreover, through the recent years I have started to use the term “comprehensive restoration” to aspire to more fundamental and multi-layered restoration that goes beyond just the formative matter. Unlike works simply using normal stone, wood, or FRP, there seems to be some sort of synergy occurring between the mass of a secondhand chest diverted in the creative process and the “comprehensive restoration”.

What in the world is it?

Take a secondhand chest for example. Sometimes the drawers are stuffed with household items, or have already been cleared out, leaving only small fragments or a few smells behind. However, these fragments or smells invite recollections of forgotten or unknown times and memories to others.

Basically, a chest is something that stores various items (fragments of the world) from its exterior to the interior and incorporates them into its own order, in other words, a reification of the frame itself that organizes such “order”. On the other hand, an old chest abandoned because of its unnecessariness is literally a hollow object separated from items that should have been sorted and organized, just meaninglessly left as ruins. It is almost like uninhabited ruins with only traces of roads and foundations remaining, a relic of the past. What’s more, the “ruins” are abandoned inside a box that is closed on all sides. In this small space, shut off and confined from the world, the memories and presence of a world that must have once been continue to drift around forever. Having in mind of such an idea, it is obvious that a secondhand chest is fundamentally different from general materials like wood, stone, or FRP and others.

In normal creative activities, artists use neutral and easily controllable materials to seek perfection that realizes their purpose or philosophy. In comparison, furniture that was actually used—such as secondhand chests—encapsulate abundant past contexts and (unknown) meanings, or “otherness” unrelated to the artist’s intentions, which acts as “noise” to become a hindrance of genuine “act of creation”.

Inversely, the situation is quite different when it comes to my “comprehensive restoration”.

As the fragments seek to be complemented in an ambiguous and multi-layered manner, the old chest encapsulating otherness is thought to form a mellow medium—a rich soil.

When I try to let the fragments, the countless connections around them, and the bundles of numerous memories and experiences arise, they provide me with many triggers and clues that transcend time and space.

When the old chest is cut into pieces, drilled, or something is embedded in it, the memories and presence from different time and space that have been stored inside tries to escape. Simultaneously, they come into contact and mingle with newly processed, embedded, combined fragments, creating all sorts of unexpected connections. Although it is not something visible, I certainly feel that way.

New intersections and connections pull various things of the past out of the darkness and encourage a new awakening. The fragments complement themselves and grow in a way that is appropriate for each of them. They form an unseen future by connecting with unexpected pasts.

The chest ceases to be a mere storage furniture of the “world” or a material for creative activities of the artist but becomes, so to speak, a new “seedbed” for the fragments (of the world)—we may possibly think this way.

The fragments grow their roots and branches within the stratum (an area that includes others unrelated to oneself) enfolding themselves to become themselves more than ever.

Like all creatures that grow by absorbing water and nutrients from Earth, they absorb and connect with the old chest’s various voices and memories from different time and space, growing vertically and horizontally, backwards and forwards, into the past and future. What Earth’s water and nutrients are to plants may be memories and history—different time and space accumulated— to the fragments, or the hollow space itself inside the old chest. The fragments gain each individual’s direction, meaning and reason, or “vitality” by connecting with the past and future.

That being said, the old chest may be an extremely fertile soil for the fragments where they sprout and grow, flourishing and transforming into something that can be called a kind of “ecosystem”.

This sort of “ecosystem” which emerges around the chest could be linked to several analogies.

Until now, it has resulted in various forms―a car lying amongst a shell mound, a lost shrine as a fictitious sacred area, a small island where various things flourish, or as a Japanese multi-tenant building where each floor (drawer) packs various matters inside them.

For example, this multi-tenant building was stacked up as a stationary real estate structure in a sculptural manner.

This time, I aim to focus on the chest’s original existence form, its autonomous (independent) and mobile nature. After all, it is present at the exhibition space from the original housing it used to be at. When I focus on the chest’s nature, being mobile and independent, it evokes an image of a wandering habitat carrying all sorts of creatures, plants and inhabitants rather than a building as a real estate (or a sculpture), shrine, or an island—maybe like Earth, a “planet” where all creatures live. Although different in scale, “chests” may be reconsidered as an analogy of a “planet” or Earth, filled with water, air and life.

Chests carry each housing’s history and lifestyle.

Each ecosystem emerging from these places as real estates, carrying inhabitants who could not rest in peace, flows out and continues to wander the world, the universe. They are like souls wandering aimlessly in the night sky, or like the twinkling stars.

ARTIST PROFILE: Fumiaki Aono

40×31×2.5cm(額装)[撮影:大河内禎]

31×40×2.5cm(額装)[撮影:大河内禎]

31×40×2.5cm(額装)[撮影:大河内禎]

32×26×2.5cm(額装)[撮影:大河内禎]

26×32×2.5cm(額装)[撮影:大河内禎]

45×57×2.5cm(額装)[撮影:大河内禎]

57×45×2.5cm(額装)[撮影:大河内禎]

45×57×2.5cm(額装)[撮影:大河内禎]

88×63×2.5cm(額装)[撮影:大河内禎]